THIS year marks the 20th anniversary of the ban on homosexuality in the Armed Forces being lifted.

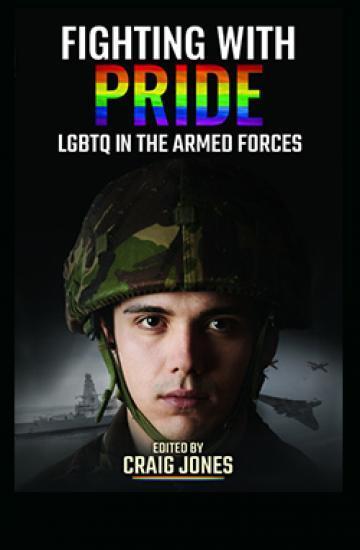

The rule on lesbian, gay and bisexual people serving in the forces was repealed on January 12, 2000. Before that date, troops suspected of being gay were subject to a dishonourable discharge. Brightonian Craig Jones is a former Royal Navy officer. He has written a book about being LGBT in the Armed Forces called Serving With Pride, which tells extraordinary stories of troops serving under the ban. Here he tells Argus reporter Laurie Churchman about his time serving in the Navy when homosexuality was forbidden.

I came out the day the ban was lifted.

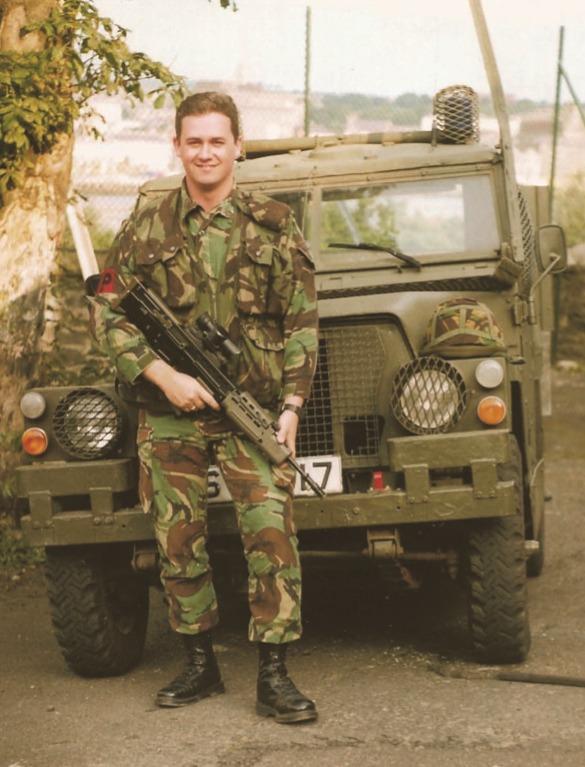

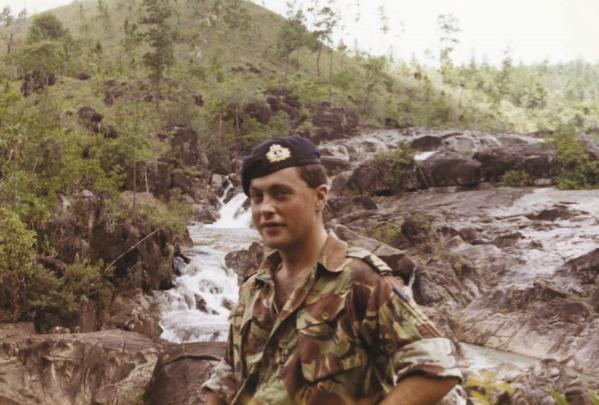

I worked in the Royal Navy as lieutenant commander. I served all over the world, from Northern Ireland to the Northern Arabian Gulf.

I knew I was gay when I joined up. Being a Royal Navy officer excited me so much I put my sexual orientation aside.

Then, in 1995, I met my now-husband Adam. Suddenly, I had something to hide which was seen as incompatible with a military career.

It was an intense experience. I spent my life looking over my shoulder, waiting for the day when the special investigatory branch of the military police might knock on my door.

All that time I was doing complex and demanding work at the front line. It was incredibly stressful.

I had to be very cautious about remembering what I said to colleagues. Adam and I moved to Brighton for our safety. There were no nearby military bases and we weren’t likely to run into anyone from the Navy.

Brighton is known for its incredible gay community. But associating with it was itself a risk.

I would say I was going to see friends of family elsewhere in the country. The reality was I was with Adam.

It was difficult when we were working away from home as well. We couldn’t write the kind of letters a couple in love would write. Sometimes they would be opened and checked.

I would call Adam using the phones on the ship and pretend he was a cousin or a brother.

It’s tough being separated from someone you love. It’s a feature of military life, but no one could be there for me. For LGBT people, it was lonely and isolating

I don’t think anybody can come up with a very good reason for why LGBT people were banned from the military.

Change in the Armed Forces has often lagged behind wider society.

LGBT people were believed to pose a threat to security.

Having gay people in the military was thought to be a risk to the leadership.

They feared being proximate to people who were gay. It was though we were all going to jump them.

I think it had something to do with showers, too. It must have been a great shock to admirals, generals and air marshals in their single cabins that there were shower curtains.

In a modern context it’s laughable.

There was also an irrational proposition that we were a risk to security because we were liable to being extorted.

The idea was that LGBT people could be blackmailed to reveal top secret information if someone threatened to out them.

But that was only because there was a ban on being LGBT in the forces.

Sergeant Darren Ford talks about this in the book.

His boyfriend forced him to stay in a relationship he wanted to leave by threatening to out him to the military police.

In the end, Darren couldn’t cope with being blackmailed and he quit the service.

The ban wrecked careers, wrecked lives and wrecked families.

Darren was on Checkpoint Charlie as the Berlin Wall came down when allegations were first made that he might be gay.

The Army flew him back from a military operation for an investigation, decided he probably wasn’t gay and then flew him back.

It was absolutely barking mad. Can you imagine the military police calling up to investigate you might be gay in the middle of a war?

LGBT people were also forced to make excruciating choices. Fighting With Pride tells the story of Lieutenant Patrick Lyster-Todd, who was asked to fight abroad while his partner was dying of Aids in Charing Cross Hospital.

He faced the very difficult decision of giving up his career or continuing with deployment knowing his partner would die while he was away. Normally, in a straight relationship, you’d immediately be given compassionate leave. You’d be supported the whole time. But he was forced to make this choice.

Many veterans have not been able to live the lives they hoped for when they signed up.

It’s not like that in the Army now.

I run a charity called Fight With Pride, which is partnered with Stonewall and the Royal British Legion.

The Armed Forces today are outstanding employers of LGBT people. All three Armed Forces are in Stonewall’s top 100 employers of LGBT people.

We’re now working with the Ministry Of Defence to look at how we can ensure veterans most affected by the LGBT ban are treated fairly.

It’s genuinely incredible.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel