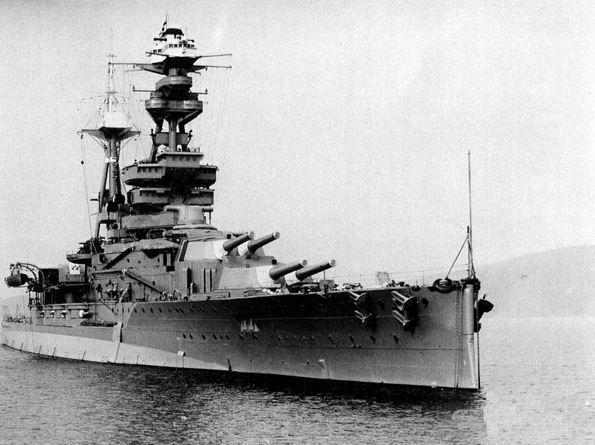

HMS Royal Oak was not a modern fighting ship but as a battleship she represented part of the might of the Royal Navy.

The Royal Navy was the ‘Senior Service’ and many people in the UK were still steeped in the “Rule Britannia, Britannia rules the waves” philosophy based on the perceived dominance of the Royal Navy. The Royal Oak was not unnaturally seen by the nation as part of this philosophy.

Many assumed that berthed at Scapa Flow, the Royal Oak was perfectly safe from attack. The night of October 13/14 1939 shattered that illusion.

Four local men were on board, three of whom survived, but Stoker Frederick W King, who would have been in the bowels of the ship with no chance of escape, did not.

Born in Lane End he was only 19 years of age when he died. He joined the Royal Navy in January 1939, following his father, also Frederick, who had served for 24 years rising to the rank of Chief Petty Officer. This included serving in submarines during World War One.

After retiring he became one of the founders and first Secretary of the High Wycombe Royal Naval Old Comrades Association. The family lived at Kitson’s Lodge on the West Wycombe Rd.

Stoker King was a keen cricketer, being captain of the Booker School team and then playing for Booker Cricket Club and the West Wycombe Estate team.

A memorial service for him was held at St Lawrence Church on Sunday October 22. More than fifty members of High Wycombe Sea Cadets Corps were present and the Royal Naval Old Comrades Association was strongly represented. Lord and Lady Dashwood “expressed their regret that owing to a sad mistake they were not present at the service, as they wished to show their respect and affection for the son of so old and valued a friend as Mr Frederick King” (Stoker King’s father).

The three local men who survived the loss of the Royal Oak included two High Wycombe men.

They were Leading Seaman Alan Babb from Hughenden Valley and Able Seaman George Williams, who were friends and rescued together. George Williams lived with his widowed mother Edith at No.51 Micklefield Rd. His father had been a police Sergeant in Wycombe, but was killed in WWI. Mrs Williams first heard the news of the sinking of the Royal Oak “on the wireless on Saturday”, but did not know that her son was safe until she received a telegram from the Admiralty on Sunday.

The third local man Henry Bryant was from Amersham and had been called up from the Reserve List, having served in WWI.

His wife and daughters had also heard of the sinking on the wireless on the Saturday and had scoured the papers that day and also on Sunday for news. They finally heard by telegram late on Sunday morning.

It is accounts like those above which really bring home the agonies which families would go through whilst waiting for news. This would be aggravated in cases like the sinking of the Royal Oak because 833 men lost their lives, two thirds of the ship’s complement.

The Admiralty would have had an enormous task to collate information and notify the families by telegram.

The Royal Oak was one of five Revenge-class battleships which had been built for the Royal Navy during the First World War. Launched in 1914 and completed in 1916, she first saw combat at the Battle of Jutland as part of the Grand Fleet.

In peacetime, she served in the Atlantic, Home and Mediterranean fleets, more than once coming under accidental attack.

The ship drew worldwide attention in 1928 when her senior officers were controversially court-martialled. Attempts to modernise Royal Oak throughout her 25-year career could not fix her fundamental lack of speed and by the start of the Second World War, she was no longer suited to front-line duty.

On the night of October 13/14 1939, Royal Oak was anchored at Scapa Flow in Orkney, Scotland, Britains greatest and supposedly safest naval base, when she was torpedoed by the German submarine U-47. Of Royal Oak’s complement of 1,234 men and boys, 833 were killed that night or died later of their wounds.

The loss of the outdated ship—the first of the five Royal Navy battleships and battlecruisers sunk in the Second World War—did little to affect the numerical superiority enjoyed by the British navy and its Allies, but the sinking had considerable effect on wartime morale.

The raid made an immediate celebrity and war hero out of the U-boat commander, Günther Prien, who became the first German submarine officer to be awarded the Knight’s Cross of the Iron Cross.

Before the sinking of Royal Oak, the Royal Navy had considered the naval base at Scapa Flow impregnable to submarine attack. The U-47’s raid demonstrated that the German Navy was capable of bringing the war to British home waters.

The shock resulted in the construction of the Churchill Barriers around Scapa Flow and rapid improvements to dockland security.

The wreck of Royal Oak, a designated war grave, lies almost upside down in 100 feet of water with her hull 16 feet beneath the surface.

In an annual ceremony to mark the loss of the ship, Royal Navy divers place a White Ensign underwater at her stern. Unauthorised divers are prohibited from approaching the wreck at any time under the Protection of Military Remains Act 1986.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here